Update #10: April 11, 2021

Foreword

It's been a while since our last update, and we've been hard at work improving and

developing the system. Around the time of our last update (late February), we had our Cumulative Design Review,

where we presented our work to UCLA faculty and alumni, who gave us very valuable feedback. These past 6 weeks

have been intensely focused on acting on that feedback, which involved lots of physical testing and new

prototyping. Because of how long it's been, we have a dedicated update from each of our 4 subteams to catch

everyone up.

Airframe

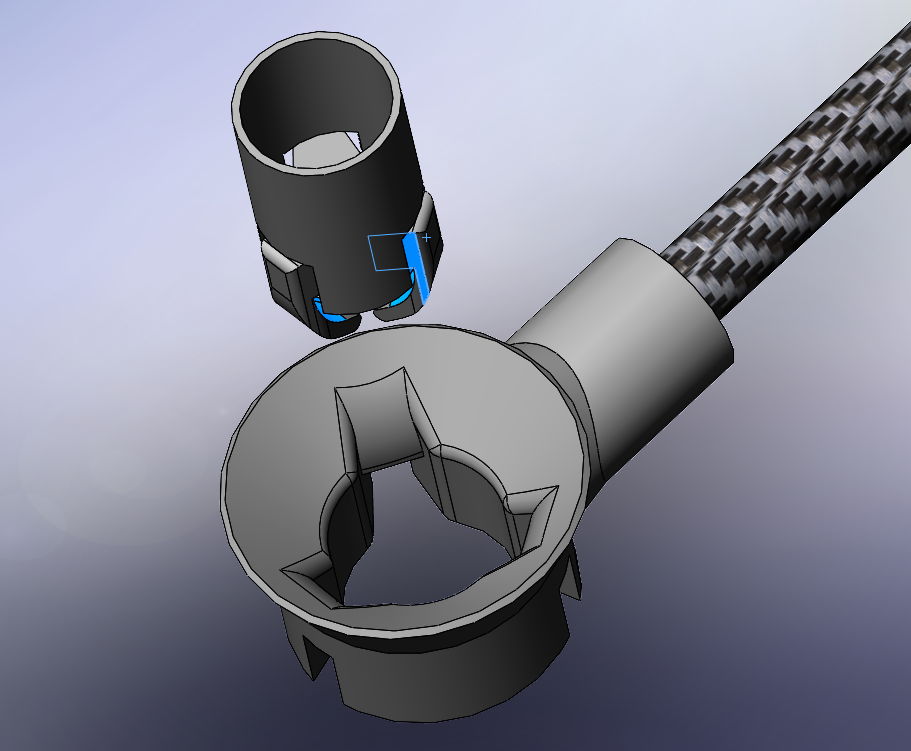

This past month, Airframe has been busy regrouping and redesigning a lot of our major

components after feedback from last quarter's design review. We are forgoing our previous docking mechanism in

favor of a more simple one, with a conical guide and cylindrically symmetric latch.

The

cylindrically symmetric latch allows us to use a single open linkage to control all of the keys that form the

latching mechanism. This means one actuator is sufficient to open and close the docking mechanism.

We are

also switching over to rectangular carbon fiber beams on our frame for ease of mounting and to minimize rotation

about the beam axis. All of these changes should make AVIATA more robust and make its failure modes much safer

for continuous flight, docking, and undocking. Thanks for following along on our journey, and be sure to keep up

with our future blog updates to see our progress!

Controls

Author: Ryan Nemiroff

We've all been hard at work since our Critical Design Review on February 19th. As with all

the subteams, the controls team received a lot of insightful feedback to help move the project forward. The two

most glaring issues from our cooperative control tests were poor yaw control and inconsistent altitude in

position hold mode. This is seen in the video below:

The drone is trying to maintain constant position, but is obviously

having a little trouble. This is partly due to imperfect PID tuning and partly due to two new realizations. One

is that neither a barometer or GPS has good precision in measuring z position, and the other realization is that

this configuration simply does not have enough torque for yaw rotation, otherwise known as

yaw authority

(and the same will likely be true as we scale up). We know this because the motors were reaching their limits in

trying to control yaw angle, and yet were not very effective. Theoretically, this knowledge could have been

obtained through calculations of the system's dynamics, but it is difficult to know exactly how much torque is

needed without more in-depth analysis. For now, we're enjoying having real life as a teacher.

To solve the

first problem of poor altitude precision, the CDR reviewers suggested we use a rangefinder to measure distance

from the ground. We gladly took this advice in the hopes that a more consistent altitude will make docking to

the frame more reliable.

Luckily the yaw authority problem also has a straightforward solution, which is to

tilt the motors to enhance the amount of torque around the z-axis. Shoutout to Dr. Brett Lopez who suggested

this, largely due to his prior experience with

hexacopters with canted motors. The

first iteration of our canted motor design tilts the motors at a 10° angle, providing at least a 3-fold increase

in yaw authority, which has shown promise in simulation. The drones have already been modified, and are just

waiting on a few more things before a real-life test.

An interesting benefit of canted motors is the ability

to translate the drone (or swarm) horizontally while staying perfectly level (as in Dr. Lopez's research).

However, this would completely upend the current control system that only knows how to move horizontally via

attitude control, so we leave it as an option to explore in the future.

Some additional ideas from the CDR

include ramping up simulated tests and running Monte Carlo simulations, which we simply haven't had the

resources or manpower to accomplish. We also got some PID tuning tips (e.g. be aware of the interplay between

the low-pass filter and derivative term), which we hope to incorporate later on. It was also suggested to use

the image targets we are already testing with as a means of measuring the “ground truth” position to compare

against GPS.

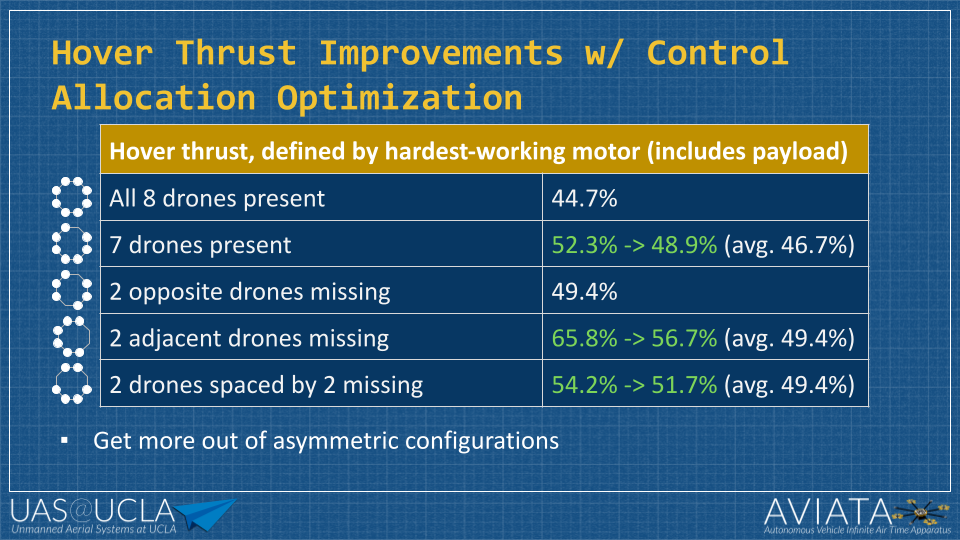

Apart from the CDR, we of course had plenty more development to get through. One item on the

to-do list that was finally checked off was optimizing the motor control allocation to achieve the

greatest-possible maneuverability in the air. Without going into too much detail, this was accomplished via a

Python library capable of solving linear optimization problems. This improves the maximum total torque of the

system, as well as the thrust for asymmetric drone configurations. The chart below shows the improvement in the

percent of max thrust at which the frame hovers.

Finally, we've been hard at work on the software architecture which must handle many different scenarios

during operation. We recently completed implementation and successful simulation of the “leader” drone handing

off its role to another drone in flight. Look out for a video of this test in the near future!

Communications

Author: Yuchen Yao

The Communication team is currently working on integrating OONF network framework with ROS2.

At this stage, I am working on implementing a bridge for serializing and transmitting ROS2 messages. Building

upon this infrastructure, it is viable to incorporate the MOST multicast protocol to the system to increase

communication efficiency. This protocol is still under heavy development. Nevertheless, this is not necessary

for the communication part to work. A simple broadcasting mechanism should be sufficient for this part of the

system to function given the nature of the control's part to work. Given our limited development time, it is

unlikely that we can implement and test the MOST protocol to its full extent. However, I think it is still

worthwhile to continue its implementation even after this project since it can make communication much more

flexible and redundant for communication in general.

Docking

Author: Axel Malahieude

A lot of work and progress has been done in the docking subteam. Our presentation at the CDR

in front of faculty and alumni went well, thanks to Puneet's work on optimizing the use of our Apriltag library

(which handles analyzing the image to find the target) and Chirag's improvements to the docking simulator. These

improvements mean that our simulator is now complete, and can reliably model any new ideas or code we want to

try on the physical drone before actually putting a real drone in danger. I presented our testing plan, which we

decided would be to succeed in landing a real drone on a paper target. If we could handle this first step, we

could then build on top of this by adding the docking mechanism and finally by doing this in-air.

March was a

very busy month. We only have 1 drone to test with, so I've been taking it out to the Van Nuys Airfield a few

times per week to do as much testing of our code as I can. As you might recall from previous blogs, the crux of

the docking logic involves 4 PID controllers, which control x position, y position, altitude, and rotation.

During these trips to the airfield, the goal was to tune these controllers such that the drone is able to

approach the target smoothly.

I started with the x and y controllers, and achieved acceptable results, but

struggled with finer tuning. This was enough for a first step, though, so I decided to give rotation and

altitude a try. Surprisingly, they worked together pretty well right away! This video shows how the drone takes

off to about 3 meters, searches for and finds the target, and begins to rotate and descend to approach it.

Afterwards, I take manual control to safely land the drone.

This video shows the same thing, but from the point of view of the

target (putting my camera face-up next to the target).

These results are promising, since they show that our fundamental logic

- using 4 PID controllers together to bring the drone closer to the target - works. The challenge ahead is

tuning these to be precise enough to be able to engage a rather small docking mechanism, rather than loosely

landing on a target on the ground. One of the biggest current hurdles is actually unrelated to docking - I've

had some issues with the PID controller on board the drone's flight controller, which I believe is causing some

instability and hindering my progress. The immediate goal is to retune this PID controller before moving back to

the docking code, and continuing to work on getting the drone to land on a target by early May.

Acknowledgment

These results are based upon work supported by the NASA Aeronautics Research Mission

Directorate under award number 80NSSC20K1452. This material is based upon a proposal tentatively selected by

NASA for a grant award of $10,811, subject to successful crowdfunding. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions

or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views

of NASA.

Join

Calendar

Officers

Gallery

Tools

Join

Calendar

Officers

Gallery

Tools